- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

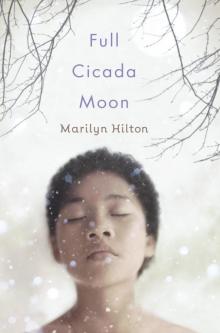

Full Cicada Moon Page 14

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 14

and I turn to see

nobody.

Then they tap my other shoulder,

and I turn to see

Timothy.

Welcome Back

What are you doing here? and

How are you? and

What’s new?

we ask each other.

I don’t hear his answers because

the music is so loud and

I’m so happy to see him again.

“Let’s go outside,” he yells,

and when we get there, I ask, “What about Wesley?”

He nods. “He was wounded, but he’ll be okay.

He’ll be in the hospital for a few months.”

“I’m so glad he’s okay,” I say.

Timothy starts to say something else, then stops

and rolls a pebble with his shoe.

So I tell him what happened

when Stacey and I came back from suspension,

how the kids switched classes, and Mr. MacDougall’s promise.

And that Stacey will be dancing with Victor for the whole night.

As we talk, a few cars crawl into the parking lot for their kids.

“You look really great, Mimi,” he says.

I’d forgotten he’s never seen me like this.

Suddenly I don’t feel like myself

in Stacey’s dress and wearing makeup,

so I wipe my lips with a tissue.

“I have something,” he says,

digging his fingers into his pocket.

“Close your eyes and hold out your hand.”

I feel something cool and round drop in my palm.

“Open,” he says.

Even in the shadows of the parking-lot lights

I see it’s a copper-colored coin

with two astronauts on the moon,

and written across the bottom:

JULY 20, 1969

FIRST MANNED LUNAR LANDING

“One small step,” I whisper.

Then say, “This is so cool. You’re lucky

to have it,” and hand it back to Timothy.

But he says, “It’s yours.”

The Party’s Over

Stacey’s mom drives up

and rolls down her window. “Mimi, is Stacey with you?”

“Um,” I say, trying to think fast.

She was supposed to see me with Victor,

not Timothy. “I’ll go get her.”

The music in the gym has stopped

and the lights are on,

but kids are still there—all in one corner—

and chanting, “Fight! Fight!”

and girls are screaming.

I try to see what’s going on,

but there are too many people in the way.

Mr. Pease and Miss Borden rush into the crowd,

easing people aside.

I follow them, and see

David Hurley sitting on Victor, punching him,

and Stacey crouching nearby, screaming at them.

Mr. Pease pulls David off Victor

and hauls him toward the boys’ locker room.

Miss Borden puts her arm around Stacey

and guides her away.

No one’s helping Victor,

who’s trying to sit up,

so I kneel next to him. “Are you okay?”

“My glasses,” he says. They’re a few feet away,

and someone shoots them across the floor to me.

His nose is bleeding,

so I hand him a tissue from my pocketbook.

“What happened?” I ask.

He shakes his head, and says,

“I gotta get out of here,”

and sits up slowly.

Someone brings him a Coke.

Chatter and silence echo in the gym

as Victor and I walk across the floor

and outside.

Timothy is talking to some kids by the curb.

“You okay?” he asks.

“Where’s Stacey?”

“She left with her mom.”

Papa is waiting in the car.

He doesn’t act surprised to see Timothy

and says we’ll take him home.

Then he asks Victor if he needs a ride.

Victor says no thanks, he’ll walk.

But Papa insists, and I’m glad

he doesn’t ask Victor why there’s blood on his shirt.

Since Never

“I was dancing with Victor,”

Stacey whispers over the phone the next day.

“Then David tapped me to dance,

but I ignored him

and danced another song with Victor.

Then Tony asked me

and I said no.

And Carl asked me on the next song,

and then David again. I kept saying no—

they were standing against the wall,

talking and staring at us—

but I didn’t want to dance with anyone else.”

“That’s creepy. But

you did look like a princess last night,”

I say, trying to make her feel better.

She keeps telling me the story.

“When the dance was almost over

David said to Victor, ‘You better let other people have a turn,’

like it was an order—and like I was a mannequin or something.

So then Victor said, ‘Hey, she can dance

with anyone she wants.’ And that’s when

David grabbed my arm—”

“I wish I hadn’t gone outside. I wish

I hadn’t left you.”

“You didn’t know,” she says. “Anyway,

what would you have done?”

“I would have piggybacked David

to make him stop.”

“You would—for me?” she asks.

Papa would remind me about raindrops

and hammers,

but this was different, wasn’t it?

So I say, “Yes.”

“Thank you,” she says, her voice softer. “Anyway,

Victor pushed him away,

but then David shoved Victor down

and sat on him.”

“That’s when I came into the gym.”

“Mimi, those boys were mad at us.”

My heart is pounding. It’s hard to hear

that this happened to my friend.

I wipe my sweaty palms on my pants.

and say, “You didn’t do anything wrong.

They did.”

I hear her swallow,

and then she says, “You’re right, Mimi.

Since when is dancing a crime?”

Making Sushi

Mama’s showing us how to make norimaki

sushi in home ec. “Put a seaweed on this makisu,”

she says, holding up the bamboo mat for rolling sushi.

“Seaweed?” Debbie asks. “Ick.”

“It tastes good. You’ll see.

Then, take this rice and press it on the seaweed.”

Miss Whittaker studies what Mama is doing.

“Mm-hmm,” she says

every now and then, and writes each step on the board.

Then we fill our rice with the cucumbers and carrots

and fish cake and sweetened scrambled egg

that Mama brought from home.

She also brought sliced hot dogs

for the girls who don’t want fish in their sushi.

I’m so happy that my shy mom came to school

and showed the girls part of herself—

&

nbsp; and part of me.

Miss Whittaker says we should save some sushi for the boys,

but everyone groans

and says the boys can make their own.

Then I say, “Only if they could take home ec,”

and Debbie calls me a rebel.

“Sushi’s good,” Linda says. “How do you say that, Mrs. Oliver?”

“Oishii,” Mama says, then says it again

slowly with Linda. “O-i-shii.”

“Please have a seat, Mrs. Oliver,” Miss Whittaker says.

I point to the empty chair at our table,

but Mama sits with Kim and Karen,

who are popping sushi into their mouths

and saying, “Oishii!”

But then

the worst thing happens.

Kim smiles at Mama and bows,

and says, “Thank you, Baka-san,”

and Karen does the same thing.

Mama’s face grows pink

and her eyes wide.

She looks at me, like she’s asking “Nani?”

I shiver,

but then she covers her mouth and laughs.

Kim and Karen look at each other,

puzzled. “Did we say it wrong?”

Mama shakes her head and asks,

“Did Mimi teach you that?”

“Yes,” Karen says. “Why?”

“She will explain,” Mama says. “Won’t you, Mimi?”

After school I have to tell Kim and Karen

what I did and why I lied,

and apologize.

“Well, it was kinda mean,” Kim says.

Then Karen giggles, and Kim giggles,

“But it was kinda funny, too,” Karen says,

and then I don’t feel so guilty.

“Your mom is really nice,” Kim says. “And she’s so cute.”

My mama is cute, and it makes me happy

they think so. But she’s so much more.

“Maybe you could

come to my house after school someday,” I say carefully.

“Sure. We can make more sushi.”

We stop at the drugstore, where we’ll go in different directions.

“See you tomorrow,” I say, heading toward Papa’s building.

Karen calls, “Okay, see you . . . Baka!”

And we all giggle until we’re out of sight.

Decisions

Someone comes into history

and hands Miss O’Connell a note.

She reads it and nods and walks toward my desk.

My pencil makes a jiggly line in my notebook.

Notes in school are never good news

unless they’re from your friend.

It says:

Please send Mimi Oliver to Mr. MacDougall’s office.

Mr. MacDougall tells me to have a seat

and sits on the edge of the desk,

clasps his hands in his lap

and makes the kind of smile

that can mean he has something awful to say.

Or it can be his way of tilling the soil.

“How are you doing, Mimi?

Are you feeling at home now at school,

making friends?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I hear good things about you from your teachers.

You’re a star student—

a real credit to your race.”

I wonder

if anyone ever said that to Mr. MacDougall,

or if he has any idea

how much it hurts.

But I nod and make a little smile

because he’s the principal

and I don’t know why he called me to his office.

He unclasps his hands and sits in his chair.

“I told you

I was going to make a decision about . . .

that ruckus you and Miss LaVoie instigated.

That’s unusual behavior in our school,

in our town.”

“I know, sir,” I say. “But I wanted to stand up for what I believe in.”

“Which is?”

I take a breath,

remember the picture on the wall of Papa’s study,

and say, “Equal rights and protection under the law.”

He leans forward. “I have to tell you, Mimi,

at first, I didn’t like what you were doing.

It was rebellious

and there’s too much of that going on

in our country these days.

But when I saw the other students

supporting your idea,

I thought differently.

And then I realized you were not rebellious

but courageous.

You know what that means?”

“It means being scared

but doing it

anyway.”

Mr. MacDougall leans back in his chair.

“You’re absolutely right. So I’ve been thinking

about girls doing wood and metal work

and boys doing cooking,

and I came up with a solution

that will make everyone happy. Starting in January,

we’ll have two new after-school clubs—

the Carpenters Club for the girls

and the Chefs Club for the boys.

How about that?”

He smiles, wanting me to say something.

“That’s great, Mr. MacDougall—

for now. But it’s not the same as having classes.”

“No,” he says, “it’s not, but we can’t have classes.

So, that’s what we’re going to do.

It’s my decision.”

He might think the subject is closed

but I know it isn’t, so I say,

“Maybe later we can have classes,”

and think Drip, drip, drip.

The bell rings, and he dismisses me.

When I stand up to leave, I say,

“Thank you, Mr. MacDougall.

You’re a real credit to your race.”

Best Prize

My last class before Christmas vacation

is science. We’re doing an experiment

to distill wood, and the room smells like burning leaves.

“Time to finish up, people,” Mrs. Stanton says.

Linda, my lab partner, and I quickly write down our results

and finish up.

The bell rings for the last time

of 1969, and we start to leave the room.

Mrs. Stanton says, “Mimi, please stay for a few minutes.”

Stacey and I are going to town after school

to shop for presents and eat sundaes,

so she says she’ll wait at her locker.

Mrs. Stanton sits at the desk next to me.

“I wanted to talk to you about something

before we all go on vacation.”

She’s smiling a different smile than Mr. MacDougall’s.

“You remember what happened last spring

with your science project?”

I say, “How could I forget?”

“That was unfortunate,” she says,

“but I was so impressed with your project—

you went above and beyond what you needed to do

for the grade.

And I know it was a great disappointment

when your moon . . . disappeared.

Many other people were, too.”

She goes to her desk, “I hope

what I have to tell you will make up for that.”

Mrs. Stanton hands me an envelope,

which has my name on it.

“At the end of school last spring,

I nominated you to join a group of students

from all over the country”—

It keeps sounding better and better—

“to go to Cape Kennedy this summer

and learn about the space program.”

“Me?” I ask.

She nods, and points to the envelope. “Open it.”

Inside is a letter addressed to me

that says exactly what she told me.

“Thank you so much,” I say, my heart fluttering. “But . . .

how much will it cost?”

Mrs. Stanton smiles and says, “It’s a scholarship program.

All expenses, including your housing and food,

and travel to and from Florida,

are paid by the scholarship.”

I didn’t win first prize last spring, but this is

the best prize.

Then I do what I never thought I’d do

to Mrs. Stanton. I hug her.

She laughs

and says, “I guess that means you want to go.”

Shopping

“This is pretty,” Stacey says, weaving her fingers

through a silk scarf draped around a mannequin.

It is blue and yellow, with irises and daffodils

and buttercups all melting together.

I bought Papa a CCR album at New Sounds,

and now we’re looking for Mama’s gift

in Cottle’s boutique.

Mama would love this scarf,

but it costs three dollars more

than I have left of my babysitting money.

Stacey had already bought presents

for her mom and dad, but today

she bought “Leaving on a Jet Plane”

for her sister, Ava, who just came home

from college in Georgia—

because Stacey likes the song.

“You should keep the record for yourself

and get Ava something else,” I say.

“You don’t buy Christmas presents for yourself,” she says.

“Then I’ll give it to you.”

“Well, where’s the surprise in that?”

“I’ll think of one,” I say,

and give her fifty cents.

Then I slip the record in my pocketbook.

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things