- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

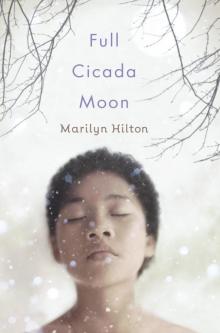

Full Cicada Moon Page 13

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 13

for quiet. We listen,

and hear a low howl sift through the trees.

“Pattress!” I call, running toward the sound.

It gets louder.

Mama and I keep calling

as we run through the woods

toward it.

We find Pattress—

she’s lying near a tree

on her side. She lifts her head when we come near

and whimpers.

Feathers surround her,

and I know Rufus is dead.

But Pattress is alive

and when I touch her, she nuzzles my hand

and tries to lick it.

Blood oozes from her torn ear

and ragged scratches on her side.

“Get Mr. Dell,” Mama says. “I’ll stay here.”

But I ask, “Can you?” I don’t want to talk to him.

“I—can’t, Mimi. You know him better.”

I don’t like Mr. Dell,

and I don’t care if he doesn’t like me.

But I love Pattress, so

I pat her head. “You’ll be okay, girl,” I say,

afraid she won’t be,

and run back out of the woods

to Mr. Dell’s steps.

“Everything will be okay,” I tell myself,

afraid I won’t be.

Wheels

I step up to the back door

and bang on it,

and bang

again,

but no one answers.

What if he’s not home?

What if he doesn’t want to answer the door?

What if he tells me to go on home?

Then I run to the garage

and bang on that door

and again.

Finally it slides open,

and Mr. Dell stands there, looking fierce.

I push away my fear

and say, “Pattress is hurt, she’s in the woods, and she can’t walk.”

“Wait here,” he says gruffly.

He goes deep into the garage

and comes out pushing a wheelbarrow

with a blanket in it. “Let’s go,” he says.

I run back to the woods,

and he follows.

It is sad and sweet

to see how tenderly Mr. Dell touches Pattress

and talks to her. “Good girl,” he says.

She whimpers back at him.

“Something got your turkey,” he says. “Probably that coyote

we’ve been hearing.”

“And Pattress tried to get it,” I say.

“She saved the rest of the turkeys,” Mama says.

Mr. Dell says, “We have to get her on the blanket

and lift her. Help me,

please.”

It’s the first thing he’s ever said to us

nicely.

Pattress’s paws hang over the edges

and her head lolls. I steady her

as we wheel her slowly to the garage.

Then we slide her onto the seat in Mr. Dell’s pickup truck.

I fold the edge over her so she’ll stay warm.

I want to go to the vet with Pattress

but not with Mr. Dell.

Mama and I walk home together

slowly.

She’s looking at the ground

and moving her lips,

saying a prayer, I think.

I don’t know who she’s praying for,

but I say one for Pattress.

Words

There has been no word about Pattress,

no words from Mr. Dell,

though I’ve been hoping for some

news—

words like

The vet said she’ll be okay,

or

She’s injured for life,

or

Thank you for finding her,

or even

It’s all your fault for having those turkeys.

But Mama and I heard none of them

while we searched for Rufus

and picked up what was left of him—

more feathers, a foot,

and part of his beak—

and buried him under a maple tree in the backyard.

We’ve heard nothing tonight

after dinner

and dishes

and homework at the kitchen table,

until

Gunshot—

the exclamation point

of a sentence with no words.

It shakes the glasses in the drainer

and rattles my chest.

Papa swings open the back door

and looks outside.

That’s when we hear the words

Mr. Dell shouts from the fence.

“You won’t have to worry about that coyote

getting any more of your turkeys.”

Thanks to Mr. Dell, the turkeys will be safe.

But I’m still worried about Pattress,

and slip under Papa’s arm.

“Is Pattress okay?” I call.

Mr. Dell shoulders his rifle.

“She’ll be fine,” he says,

and nods

so deeply that it could be a bow.

Pardons

Toshiro Mifune had been living in our house

since last night, when

Walter Cronkite showed President Nixon

pardoning a turkey

so it wouldn’t get eaten for Thanksgiving.

Now my mama has returned, and says,

“Mimi-chan, draw a big sign—

Pardoned Turkeys—

and put it in the front yard.”

Then her eyes fill with tears for Rufus.

We come up with a plan:

Anyone who wants a turkey

has to sign a paper

promising they’ll keep it as a pet

and let it die in its sleep

after a good, long life.

I tell Mama, “Rufus would be happy to know

he saved all the other turkeys

from Thanksgiving dinner.”

Mama wipes her eyes,

and I make the sign and type the promise

on nine pieces of paper—one for each turkey.

Pattress will be okay, and now

the turkeys are pardoned.

I run to the coop and tell them

they have something to be thankful for.

Homework

Stacey and I are doing homework together

in her bedroom. It’s the first time I’ve been to her house

since she invited me in May.

Her house is smaller than mine,

but they have a garden in the backyard.

In the middle sits a silver ball on a pedestal

that reflects things almost all the way around.

She calls it a gazing globe,

and when I go home tonight

I’ll ask Mama if we can have one,

so we can see the moon and the stars

without looking up.

I’m propped on Stacey’s big bed,

and Tinkerbell, her cat, is stretched out beside me.

Her purring sands the air.

Stacey looks up from her history book

and puts her head in her hand. “What are you wearing to the dance?”

“Oh,” I say, marking my place with my finger. “I’m not going.”

She lifts her head. “Why not? Oh . . . ,” she says,

remembering what happened last spring.

“I’ll stay with you the whole time. I promise, Mimi.

So, will you go?”

“Why do you want me to so bad?”

“Because dances are fun . . .

and . . .” She looks at her book.

“What?”

“Well, do you like Victor? I mean, like him.”

“No, but you do.”

She waits for me to say “That’s dumb” or “That’s great.”

Instead I ask, “Did you tell your mom?”

“No—never!” she says.

Then she sits next to me on the bed.

“I’m sorry, Mimi. I didn’t mean it that way.”

I know what way she meant,

but I don’t want to talk about it with her.

She and Timothy are the only people

who don’t make a big deal

or act funny around me,

and I don’t want that to change.

But she talks about it anyway:

“You know Mother. I mean, look how long

it took for her to invite you over.

She never invited my Black friends back home.

I’m so sorry about that.

I don’t care if Victor is Black. I don’t care

if he’s dorky. Actually,

I like that about him.”

“That he’s Black or he’s dorky?” I ask,

stroking Tinkerbell. “Or maybe you like him

because your mother won’t?”

She pets Tinkerbell, then says, “No, I’m sure

that’s not why. He’s just interesting and smart and nice.”

“And cute?”

Stacey giggles and covers her mouth. “Yeah,”

she says, and falls onto the bed.

“So, do you like me because I’m Black and Japanese?”

“Wha-at?” Her face tells me I’m so wrong. “Of course not,

Mimi. I like you because you’re brave

and dorky.”

And we both laugh.

“So, why do you like me?” she asks.

“Because . . . you don’t care

what people think,

except when your big toe is showing.”

“Oh, that!” she says, and giggles. “That was a disgrace.

And then we caught the cooties.”

“Cooties are stupid.”

Then Stacey rolls over and says, “I was wondering if . . .

you would pretend to be at the dance with Victor

if anyone asks.”

“Do I have to hang around him

and dance with him?”

“No, I want to do that. But, like, if my mother asks.”

“Okay,” I say, “but I don’t think you have to worry.”

“There’s something else . . . ,” she says. “Do you think your mother

would make me a dress?”

“I’m sure she would, but you have so many cute ones.”

“Your mom makes beautiful dresses,” she says.

“And I want to look beautiful. If you want,

you can wear one of mine to the dance.”

“Like from Bonwit Teller?” I ask.

“From anywhere!”

Then, we forget about our homework

and talk about the dance—how we’ll switch dresses

and become each other.

But we don’t talk anymore about why

she wants to keep her crush on Victor a secret.

Thanksgiving

Mama wanted to keep Shirley and Bobo,

but the other seven pardoned turkeys

went to good homes before Thanksgiving Day.

On Thanksgiving morning, she packs vegetables

and mashed potatoes, a pumpkin pie,

and a cooked chicken (because it was already roasted at the store)

in a cardboard box.

“Take this to Mr. Dell,” she tells Papa.

“He is all alone.”

This is how Mama will till the soil

with Mr. Dell.

“Come with me, Meems,” Papa says.

I shake my head. I don’t want to see Mr. Dell.

“It will be easier to carry the food

in two boxes, so I need your help.”

“Well, okay,” I say, “as long as I don’t have to talk to him.”

We carry the boxes across the yard

and over the fence to Mr. Dell’s back door,

and knock

and knock again.

Just when I’m about to say “Let’s leave them here,”

the door opens

a crack

and then wider.

Mr. Dell doesn’t smile,

but he doesn’t shut the door.

“Emiko made dinner for you,” Papa says,

and holds out his box.

Chicken-smelling steam seeps through the flaps of my box,

and then a miracle happens—

Mr. Dell opens the storm door all the way

and takes Papa’s box.

I stack mine on top.

Mr. Dell looks at us

and says, “Thank you.”

“Happy Thanksgiving,” Papa says.

We walk side by side

all the way home

before we look at each other

and smile.

Winter Again

Another Try

I’m getting ready for another dance with Stacey,

and it feels the same as last time.

I wish Timothy was in Hillsborough

because, even though Stacey promised to stay with me,

I’m nervous

and want to see my friend

and laugh with him

and maybe even dance together.

Would he want to dance with me?

Papa gave me another dime before I left,

but I said I wouldn’t need it this time.

He put it in my hand anyway

and said, “You never know.”

The dress Mama made for Stacey

is emerald-green velvet

with an empire waist and Juliet sleeves.

“You’ll be the princess tonight,” I tell her,

and she asks, “You think Victor will notice?”

I shrug because I don’t know what boys think,

and because a little part of me doesn’t want Victor to notice,

because then I might lose a friend.

I’m wearing one of Stacey’s dresses,

an A-line style made of garnet-colored silk brocade.

It shimmers in the light.

Stacey says, “You’ll be the belle of the ball.”

We giggle. Secretly,

I think the dress Mama made is prettier.

This time, Stacey doesn’t have to help me

put on blusher and eyeliner and shiny lips

because I’ve been reading the Co-ed magazines

in the home ec room. And I’m wearing

the happy moon pendant

from Timothy

to give me courage tonight.

“You ready, girls?” her mom says in the hall. “Time to go.”

Her dad takes pictures

and says we’ll knock the socks right off the boys,

and her mom gives Stacey a bracelet to wear

just for tonight.

“All parents are the same,” I say,

and we giggle again

because it’s true

and we’re both nervous.

As her mom drives us to school,

the streetlights seem to bow

to the princess an

d the belle.

Winter Magic

This dance will be different, I tell myself,

because I am older and wiser than last spring.

This time, I don’t swallow giggles,

and I don’t expect something brand new to happen.

As soon as Stacey and I hang up our coats

and go into the gym, she begins to dance

to “Love Child,” and looks around for Victor,

her eyes glittering.

“Do you see him?” she asks.

As I look,

some girls and even some guys

smile at me or wave, and I know

this dance will be different.

“Don’t worry,” Stacey shouts close to me

over the music, “I won’t leave you,”

and just then, Victor comes behind her,

catches my eye,

and taps her shoulder.

She twirls around and looks surprised—

but who else was she expecting?

“Hi,” she says shyly.

“You just get here?” he asks.

We nod because yelling hurts our throats.

The music switches to “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,”

and the three of us start wobbling

like a three-legged stool.

It only takes a minute

for the two of them to be dancing with each other

and for me to be dancing with myself.

Suddenly I’m thirsty,

and point to the refreshment table.

But on my way there, I get stopped

by kids saying hi.

And then,

Michael from my homeroom asks me,

“Wanna dance?”

No one ever asked me that before,

not even Papa or Auntie Sachi.

The band is playing “I’m a Believer,”

and I’m laughing, and Michael’s laughing

because we’re doing different moves

in opposite directions.

Then Stacey and Victor come over,

and we all dance together in a circle.

The song ends

and we’re puffing and sweating, and

I don’t know what to say to Michael

or what to do,

so I say, “Excuse me,”

and I head to the refreshment table.

Someone taps my shoulder,

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things