- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

Found Things

Found Things Read online

For Ann and Steven, who were my first best friends

“Hope” is the thing with feathers— That perches in the soul—

—Emily Dickinson

Chapter 1

The morning after Theron leave us, I start talking this way—like no one else I’d ever known in Quincely, New Hampshire. Whenever Mama heard me, she look like she just ate a purple plum and didn’t know what to do with the memory of it, all sweet and sour mixed together in her mouth. But the only thing she say was that miracles are what’s left after everything else is used up, and one morning I’d wake up and talk just like her River again.

I noticed that she never say one day a miracle would bring Theron back to us. Maybe that was too much to hope for. Theron leave us in early March, and the hole that remain grew wider and deeper and more raggedy as each day pass.

By mid-May he still hadn’t returned, but I found out there were worse things than talking peculiar. I could have been that new girl, Meadow Lark, with the popped-out eye and her lurchy way of walking. She have a pretty name but it was one of the only things pretty about her. In homeroom she stood up and introduce herself, just like everyone had to do on their first day. Meadow Lark Frankenfield smiled when she say her name, not like most new kids, who stoop and mumble, or look at their shoes and turn red, and then collapse into their seats and cross their arms. Meadow Lark kept standing, and touch her blue-frame glasses as if she expected questions. But no one ask her anything.

Most kids probably couldn’t have told you her real name thirty seconds later, but by F period, just before lunch, they were already calling her Frankenfemme. Daniel Bunch started that. He say it was a French word. I don’t know French, but you could tell he’d already drawn out a space and put Meadow Lark where she belong in it.

Anytime a new kid start, everyone who is already here rubs the smudges off themselves and act like the spoons from the good drawer, a little shinier than the everyday ones. Sonya Mittell bounces her ponytail higher, DeWayne Green puts more drama into his jokes, and Martin Delboni hunches deeper into his shoulders. Teachers talk like radio ads and show more gum when they smile and call on everybody, not just the usual kids. Everyone brightens up when a new kid start, because they want the new kid to go home and say what a great school it is and what interesting and shiny people go there.

But for Meadow Lark Frankenfield, that didn’t happen. If it didn’t happen the first day, it wouldn’t ever happen. Something was wrong with her—not just her popped-out eye, but with her whole body. She walked as if her leg was glued on backward, like a car rolling along with a flat tire.

I was eating lunch in the quad and watching her that first day, when Daniel Bunch come by.

“I see you looking at Frankenfemme,” he say, sounding so proud of the name he’d given her. No one but Daniel ever talked to me at lunch anymore, though you could never call what we say much of a conversation. “Taking notes?”

I had just bitten into my sandwich when he come along. I looked down at my sneakers and chewed, wishing he’d just go away. I didn’t want to see him, and I didn’t want to see that cast on his arm because it reminded me too much of Theron.

But he stopped in front of me, and I felt his stare. “You two have a lot in common, she being the same kind of trash as you.”

Then he got up real close to my face and whispered, “You know what your brother is, right?”

Keep looking down, River, I told myself, as the sandwich in my hand quivered. I thought of all the things Daniel might call Theron—a runaway, a coward, a fugitive—or maybe he was about to call him trash, too. I’d heard all of them, but I wouldn’t have called my brother any of them.

“I’ll tell you,” Daniel say. “A wimp.”

He is not a wimp, I thought, and blinked.

Daniel tapped his cast. “And a drunk—the worst kind of drunk, the kind that drives into rivers and then runs away. If he ever comes back here, he’ll pay for it. They’ll throw him in jail for it.”

Daniel kept his face up to mine, like he was waiting for me to say something, and hoping I’d look at him. All I could think about at that moment was not inhaling his ham-and-mustard-smelling breath and not crying in front of him. And that he could have come up with a better word than “wimp.” Funny that Daniel thought he was so smart, when everybody knew he had to repeat fourth grade.

“And don’t clamp your jaw like that,” he told me.

My eyes squeezed narrow, and I pressed my sandwich until the jelly oozed out. Theron started paying for what he did the night it happened, and none of those words—“runaway,” “deserter,” “fugitive,” “wimp,” or “drunk”—were true. They couldn’t be.

Theron. The thought of him caught my heart.

Finally, after what felt longer than January, Daniel pulled away, but he left his nasty breath with me.

So when Meadow Lark come over and sit beside me on the bench a few minutes later and held out her open bag of Cheetos, I got up and went to Ms. Zucchero’s room to work on my collage.

No one else was there except Ms. Zucchero, who ate carrots one by one from a lunch bag while grading artwork, so I sat at the big butcher-block table in the middle and spread out my collage. I’d put almost everything I’d ever found on that collage. It was going to be a present to Mama, so it had to be perfect and it had to make her smile.

I laid the little string of gold-colored beads, the bent watch face, and the tiny key on the table. I took six colored pens from the bin and set them down. Glue, scissors, colored paper, paper punches next to them, and then I started to sort, and place and replace, and then glue and write.

Lately when I worked like that, something strange happened. It was hard to understand, but my mind wandered around inside a house. I’d never seen that house before, but it felt as familiar as the smell of my pillow. My mind slipped into that house and walked around in it while my hands worked, so stealthily that I never realized I was there until something interrupted me.

That day while I worked on my collage, my mind went to a pantry room off the kitchen. This was a new room, but I could tell you everything in that pantry (cans of Campbell’s soup and Ever Fresh tomatoes, blue-and-white sacks of flour and pink sacks of sugar, and store-brand Cheerios and oatmeal), the color of the walls (spring-leaf green), and the smell when you go near the shelves (onions and oregano).

Ms. Zucchero say something to me, and quick as spit I was back in the art room and realized I’d been in the pantry of that house.

“Tell me about the beads.” Ms. Zucchero was pointing to the three gold-colored beads on a string. Her fingernails were painted dark purple, and the one she pointed with had a little chip.

The glue the beads sat in was still white, and I pressed them until they hurt my finger.

“I found them in the river. They’re just plastic.”

She leaned over the beads for a few seconds. “No, I think these beads are real gold. My aunt had some just like them. What else did you find?”

I looked at everything glued onto my collage, and pointed out each one to her one by one. The glass pieces—green, red, purple, deep blue—all brushed soft by the water and sand of the river. The porcelain doll head with the nose buffed off, the piece of wood that looked like a hand, the tiny bald plastic baby with arms and legs and head that moved, a black bear’s tooth, the peach-colored leaf that was still soft, an R typewriter key, a bottle stopper made of glass, the bent watch face, the stone that looked like a face, the gold-colored beads.

Ms. Zucchero put her hands behind her back and took another close look. “They all tell a story, don’t they?” she say, and then went back to her desk.

�

�I guess so.” I never thought they had a story. They just showed up on the sandy beach at the river.

“I hope I can hear that story one day.”

The wall clock say it was almost time for A period, but I wanted to glue one more thing, a tiny metal iron, before then. And I wanted to go back to that pantry, where behind the flour was a jar of chocolate bits that I knew tasted bittersweet. Instead I thought about Meadow Lark Frankenfield and how I’d left her on the bench by herself—but not before I smiled just enough to let her know I knew what she did for me.

Meadow Lark wasn’t pretty, but you could tell she was a cared-about girl by the straight cut of her pumpkin-colored hair and her smooth fingernails. And that bag of Cheetos come out of a paper bag with her name written in curlicues. When she pulled out the Cheetos, a napkin fell out with a tiny red heart drawn in the corner. Someone cared about Meadow Lark and whether she had nice hair and fingernails and a good snack. But even though she come over to the bench after Daniel went away, I knew that her eye and the crooked way she walked would take some getting used to.

Chapter 2

“Daddy,” I asked that night, “am I pretty?”

“Everything about you is pretty, River,” he say. “Especially your name.”

Daddy told me all the time how when he and Mama brought me home that first day after they knew I was theirs, they didn’t change my name because it was already too perfect. I knew that like I knew the sound of their voices, but that night I needed to hear it again.

Then, as always, Daddy and I got quiet and listened to the dusk. That’s when the things of the day and the things of the night switch places, and everything blurs. It’s when Daddy rolls back the awning over the deck and we watch the stars grow in the sky. It’s the time of day, Mama say, when angels abound, and if you’re very still you can hear the rustle of their wings descending.

Sometimes I wondered what Daddy thought about at dusk, now that Theron was gone. Did he think about Theron and where he might be, and how Daddy didn’t stop Theron when he say he was leaving us and promised he’d never come back? That’s what I thought about, but I knew dusk was a special time for Daddy—almost a sacred time—so I never asked him about those things on my mind.

After night settled over the sky and tucked us under it, when it was okay to talk again, I asked Daddy if he’d ever seen an angel.

His mouth wrestled a smile. “Besides the one I’m looking at now?”

When he talked like that, I knew that I, too, was a cared-about girl, even with that feeling in the back of my heart that I belonged somewhere else.

Then he leaned over so far to me that his beach chair squeaked and say very low, “Between you and me, I don’t believe in them.”

At that, Mama’s voice come through the kitchen window behind us. “Ingram, you can’t find what you’re not looking for,” she say as one plate clacked against another. “But if you look hard enough, you’ll find it.”

Mama was always saying things like that—don’t wash your hair every day, be kind to your enemies, forgive and be free—and now this: You can’t find it if you’re not looking for it.

Daddy shrugged and then whispered, “She believes, and that’s all that matters.”

I looked up at the sky, which was mute and dotted with stars. I wanted to believe like Mama did in invisible things, and I wanted to believe that Theron might one day come back to us. So, even though I had as much confidence as Daddy in angels and miracles, I found a star and whispered so soft that anyone listening would have had to read my lips, “I wish I had the eyes to see.”

When I walked past Theron’s room on my way to bed, his smell was, as usual, still there. Cinnamon toothpaste, sweaty sneakers, and his shampoo with the pine-tree fragrance. And that sun-warm-skin smell that’s only his. Theron’s scents hovering in his room made me ache to see him again. I stepped one foot inside and touched the things on his bureau that he touched probably every day: his hairbrush, his silver dollar from the river, his picture of Shawna, the all-star trophy he got after he began to “straighten up,” as Daddy call it.

I stretched my arm to touch the spot on his trophy he’d have touched so many times—on the shoulder of the baseball player winding up for a pitch. It would be just like Theron to touch the shoulder. Other people might have remembered different things about Theron, and some of them not very nice, but what I remembered was his hand on someone’s shoulder.

“River Rose Byrne, don’t you put another finger on that statue!”

How Mama slipped up the stairs so softly was one of the great mysteries of the ages. She stood in the hall with her hands on her hips, the silhouette of her head blocking out the ceiling light.

My hand snapped back. “I just—”

“I know what you’re up to. You keep your hands off your brother’s things. What will he do when he comes back and sees fingerprint smudges on his trophy?”

“Probably turn around and go back to where he come from.”

I expected Mama to say, “Came, River,” as usual, but instead she dropped her hands from her hips and pressed her lips together tight, and I realized that was exactly what Mama feared. I wanted to say, Mama, don’t get your hopes up so, because I don’t believe he’ll ever come home. He left here so mad and determined, so full of pepper and pain, that we will never see him again.

Instead I say, “I was only kidding, Mama,” because what else could I tell her as she stood in Theron’s doorway with her face so full of wishing for him to come home?

Chapter 3

I couldn’t stop thinking about what Mama and Daddy say about angels and being watchful. As if my wish began to draw breath while I slept, the next day I decided to focus my eyes in a new way. The first thing I noticed when I woke up was that Mama wasn’t humming in the kitchen. For as long as I could remember, every morning Mama had hummed in the kitchen, but this morning I realized that she hadn’t done that since Theron went away. Most times I didn’t want to hear it anyway, being so sleepy that it made my bones itch, but this morning I realized how much I missed that sound.

Mama wasn’t even in the kitchen that morning. I found her sitting on her bed, tracing her finger along the chenille pattern of their bedspread. The room smelled spicy of aftershave, and Daddy come out of their bathroom smoothing the gray hair above his ear.

“Where you going today?” I asked.

“Just down the track to Boston.”

We both looked at Mama, and I say to her, “Don’t worry—he’ll be back tonight.”

Daddy worked as a train porter, and Boston was one of his shortest runs. When he went down to Boston, he was back home again almost before we knew he had gone. It was like he had a regular job.

“I know that,” Mama say, and nodded. “Just please, Ingram, don’t be late coming home.”

There was a look between them then, as alive as a violin string pulling out a last note, that made me hold my breath until Daddy answered her. “As long as there’s coal in the bin and the rails don’t buckle.” It was what he always say when she worried that he wouldn’t come back.

Mama smiled, and my new eyes opened again and saw that she was wearing her red lipstick. She looked so pretty. Maybe she wanted Daddy to think so too, so that when he traveled far away, he’d always want to come home.

At school I watched the clumps of kids in the quad before the first bell, and the teachers in my classes, and then my tennis shoes running the track in PE. I imagined looking at everyone through the prism Mama kept on the kitchen windowsill, all of them appearing stretched and rainbow. Seeing things differently wasn’t so hard. The hard part was knowing exactly what I was looking for, though I sensed it could be right around the corner.

That good feeling lasted only until lunch, when Daniel come to me again and my day shrank into its usual colors. I rubbed my apple hard on my sleeve, to make it look like I didn’t notice h

im, but that didn’t work. As he strolled by me, he muttered, “I’m watching you. Always watching you,” spending extra time on each W sound.

After he passed, I looked up and saw Meadow Lark Frankenfield. Just like the day before, she come and sat on my bench and opened her curlicue bag.

I wanted Cheetos today and would have taken one when she offered it, but instead she pulled out a bag of pretzel sticks. Pretzel sticks are what you get when everything else in the snack pack is gone. So when she pulled open the bag of pretzels and held it out to me, I stared at her. I stared and didn’t say a word. It felt good.

Then she looked away and reached into that bag and put a pretzel stick in her mouth. As she did, a strand of her hair slipped in with it. It had felt good to stare and not say a word when she held out that sad bag of pretzel sticks, and it felt even better to watch her chew on a strand of her own hair.

“I’m not working today,” Mama had told me that morning soon after Daddy left. “So bring home a quart of milk after school.”

When Theron was here, she brought home a gallon every few days from Shaw’s, where she worked. But now that he was gone, even a quart went sour before we used it up. Mama used to say we went through so much milk that we should buy a cow and put her in the backyard, but she never said that anymore.

“Don’t stop along the way—and you know what I mean,” she told me as she handed me a five-dollar bill. Mama could smell the river and knew if I have been near that water.

I knew exactly what she meant. Buying milk gave me a reason to walk down along the river, my magic place. Something about the river, especially in spring when it rippled and ran high, pulled me toward it, and I couldn’t ever walk by it without paying a visit. I’d tell myself, You just keep going, but before I knew, I’d be walking down the path in back of the library to the sandy beach, and tugging off my sneakers and socks and rolling up my jeans past my knees. Then I sat on the big, flat rock fixed halfway into the water.

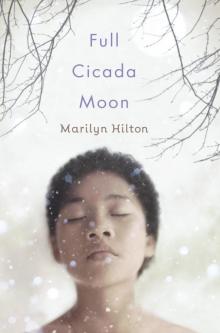

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things