- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

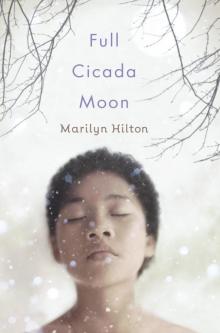

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Read online

DIAL BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA/Canada/UK/Ireland/Australia/New Zealand/India/South Africa/China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2015 by Marilyn Hilton

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hilton, Marilyn.

Full cicada moon / by Marilyn Hilton. pages cm

Summary: In 1969 twelve-year-old Mimi and her family move to an all-white town in Vermont, where Mimi’s mixed-race background and interest in “boyish” topics like astronomy make her feel like an outsider.

ISBN 978-0-698-19127-3

[1. Novels in verse. 2. Racially mixed people]—Fiction. 3. Sex role]—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.5.H56Fu 2015 [Fic]—dc23 2014044894

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Front Cover Girl Image © Terry Husebye, Getty Images;

Additional Images Couresy of iStock

Jacket Design by Lori Thorn

Version_2

For

Keiko and Robert, Lois and James Wesley,

and their families

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Flying to Vermont–January 1, 1969

Hatsuyume

Waxing Gibbous

Reflections

Arriving

New House

First Night

Like Saturday

Next Door Boy

Ready for School

First Day

Rules

Shop

Getting to Know You

Obento

Hungry

Journal

Notions

Science Class

Little Lies

Downtown

Farmer Dell

Others

Winter

Karen and Kim

Cooties

Notes

Detention

Science Project

Stars

February Vacation

The Soda Jerk

A Girl Who Twirls

Skating Pond

Rendezvous

Snowfall

Snow Day

The Mouse Takes the Cheese

Consequences

Tears on Glass

Life in 1968

A New Outlook

Spring 1969

Crocuses in the Snow

Kimono

Relocation

Liars

Moving Forward

Stacey’s Birthday

Light and Dark

If I Had a Hammer

Poults

Math

Something Important

April Vacation

Inheritance

April Moon

Hope

Secrets

Weirdos

Sea of Tranquility

Sign of Spring

Water and Dirt

One-Way

Mama’s Visitor

Spatial Reasoning

Looking Forward

Kind Of

Moon Viewing

The A Group

Best Friends Always

Dress, Hair, and Makeup

Spring Thing

Science Groove

No Words

Full Missing Moon

Bad Dreams

Learning Japanese

Party Snacks

The End of the Beginning

Summer 1969

The Question

Pie, the Moon, and Stacey

Magicicadas

Apollo 11

Room of Kings

Remember This Night

The Real Thing

The Answer

Good News and Sadness

Language

Tilling

Babysitting Baby Cake

Going Home

Jitter Legs

One Small Step

Eighth Grade

New Boy

We’re Having Mr. Pease for Lunch

How to Make Corn Bread

Victor

Crush

Fall 1969

Sit-in

Civil Disobedience

The Principal’s Office

Suspended

Fine

Bad News

The Way We Say Good-bye: One

The Way We Say Good-bye: Two

Reformed

Switched

Promises

Where’s Pattress?

Wheels

Words

Pardons

Homework

Thanksgiving

Winter Again

Another Try

Winter Magic

Welcome Back

The Party’s Over

Since Never

Making Sushi

Decisions

Best Prize

Shopping

In the Mirror

Excuses

The Exchange

Expressions

Visitors

Gifts of the Magi

Oshogatsu—January 1, 1970

Confessions

Vermont Neighbors

Full House

This Year and Last Year

Adventure

Full Cicada Moon

Acknowledgments

Glossary of Japanese words in FULL CICADA MOON

Word List

Be loving enough

to absorb evil

and understanding enough

to turn an enemy into a friend.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“That’s one small step for [a] man,

one giant leap for mankind.”

—Neil Armstrong

Flying to Vermont–January 1, 1969

I wish we had flown to Vermont

instead of riding

on a bus, train, train, bus

all the way from Berkeley.

Ten hours would have soared, compared to six days.

But two plane tickets—

one for me and one for Mama—

would have cost a lot of money,

and Papa already spent so much

when he flew home at Thanksgiving.

Mama is sewing buttons on my new slacks

and helping me fill out the forms

for my new school in Hillsborough, our new town.

This might be a new year

but seventh grade is halfway done,

and I’ll be the new girl.

I’m stuck at the

Ethnicity part.

Check only one, it says.

The choices are:

White

Black

Puerto Rican

Portuguese

Hispanic

Oriental

Other

I am

half Mama,

half Papa,

and all me.

Isn’t that all anyone needs to know?

But the form says All items must be completed,

so I ask, “Other?”

Mama pushes her brows together,

making what Papa calls her Toshiro-Mifune face.

“Check all that apply,” she says.

“But it says just one.”

“Do you listen to your mother or a piece of paper?”

I check off Black,

cross out Oriental,

and write Japanese with a check mark.

“What will we do now, Mimi-chan?” Mama asks,

which means: Will you read

or do algebra, so you’re not behind?

“Take a nap,” I say.

Mama frowns,

but I close my eyes

and pretend we’re flying.

The bus driver is the pilot

and every bump in the road

becomes an air pocket in the sky.

Hatsuyume

A jolt wakes me up. I was dreaming

my hatsuyume—the first dream of the new year.

If I tell my hatsuyume, it won’t come true

because in Japanese, speak sounds just like let go.

And if my dream meant good luck, I don’t want to

let it go.

I dreamed I was a bird, strong and brown

and fast

with feathers tipped magenta and gold.

I shot straight up into the air like a Saturn rocket,

then swooped and dove, the sun warming my back.

I pumped my wings, then glided

over the desert

and the sea.

The air filled my lungs,

the wind lifted my wings

higher and higher

over the mountains

and above the clouds.

The moon grew large,

and I stretched to touch it.

Maybe it was a good-luck dream

and this will be a good year

for Papa and Mama and me.

That’s what I hope.

But, what if my hatsuyume meant bad luck?

Mama says to let go of your bad dreams by telling them.

Papa says to bury your bad dreams

in a hole as deep as your elbow.

The ground in New England is frozen,

so if I listen to Papa, I’ll have to wait until spring.

I’ll listen to Mama instead

and write my dream on paper,

so either way—good luck or bad—

my hatsuyume will not be spoken.

I have never flown before

but one day

soar.

will

I

Waxing Gibbous

I study

The Old Farmer’s Almanac

that Santa had put in my stocking

from cover to cover.

I like

reading about the moon,

and I’ve memorized

all its names and phases.

I know

the moon tonight

is waxing gibbous, almost

the Full Wolf Moon.

It has chased us outside the bus window

all the way from Boston,

bounding through the sky,

skipping across rooftops,

dodging trees

like it has one last word

to tell us.

I remember

Papa said

if you leave eggs under a waxing moon,

all your chicks will hatch.

And Mama said

if you make a wish on the moon

over your shoulder,

it will come true.

I whisper

to the moon on my shoulder:

“I wish

all my dreams will hatch.”

Reflections

This bus lulls.

Some people are reading, some are sleeping,

two ladies behind us are talking,

the baby up front chuckles hoarsely,

someone is sipping tomato soup,

and in back, Glen Campbell is singing “Wichita Lineman” on the radio.

All of us who don’t know one another

are riding together on this Trailways bus to Vermont

on the first night of 1969.

It doesn’t feel like oshogatsu, New Year’s Day,

because Mama couldn’t make ozoni and sushi

and black-eyed peas and collard greens,

and we couldn’t sip warm sake from the shallow cups.

Mama says she doesn’t care about those things

because we’re traveling to meet Papa.

But what bothers her

is that no man crossed our threshold this morning

(because we don’t have a threshold today),

and that means we’ll have bad luck all year.

I told her we can find a man to visit our new

house,

but she said, “Too late.”

The lady across the aisle is knitting a scarf.

She has been staring at Mama and me

ever since the sun set.

I want to stick out my tongue at her reflection in our window

just to let her know

I know,

but that would disgrace Mama

and disappoint Papa.

So, I open the Time magazine

with the three Apollo 8 astronauts on the cover—

the Men of the Year—

that came just before we left,

which Auntie Sachi slipped into my bag at the door,

with a note:

Have a safe journey.

Arriving

I can tell by the way Mama looks at herself

in the window, brushes her bangs to the side,

and runs her finger under her eyes

that we’ll be in Hillsborough soon,

where Papa, in the tweed coat he calls “professorial,”

will meet us.

She pops a wintergreen Life Savers in her mouth

and passes the roll to me.

I take one

because I want my kiss on Papa’s cheek to be fresh.

The bus slows down.

A barbershop, an insurance company,

a dentist’s office, a grocery store

all slide by. The air prickles

and everyone sits up straight and shifts in their seats,

finishes talking to the person next to them.

“Hillsborough coming up!” the driver calls.

The lady across the aisle winds up her yarn

and tucks her knitting into a tote bag. She looks at me again

and leans into the aisle. “Are you adopted?”

“Nani?” Mama asks me. She must have been daydreaming

or she would have asked, “What?”

I whisper, “She wants to know where we’re going.”

Mama glances at the lady and turns into Mifune.

But before she can pretend she doesn’t speak English,

I say, “She’s my mom.”

The lady looks at me, then at Mama,

and shakes her head.

The bus pulls up in front of a diner

and stops so quick

that we all jerk forward in our seats.

The driver cranks a handle and

the door hisses open.

He disappears outside

as cold air scampers down the aisle.

Papa is waiting in front of the diner

wearing his coat

and a red-and-gold scarf, Hillsborough College colors.

When he sees me inside the bus, he waves.

But I wave harder.

Outside, I hold his hand in his pocket

while he counts our suitcases—four plus my overnight case.

The icy air pinches my cheeks,

but my heart is warm.

He drapes his scarf around my throat

and says, “Now you’re the professor.”

The knitting lady steps down from the bus

for a breath of air.

“And this is my dad. See?” I say, and smile.

She looks at Papa, at Mama,

and back at me. Then,

not smiling, she says, “Yes, I see,”

and walks toward the diner.

When I know Mama and Papa can’t see me,

I stick out my tongue

so far that it hurts.

New House

Our new house smells like varnish and

balsam needles and mothballs.

The floors are all wood, except the kitchen and the bathrooms,

which are linoleum,

and they creak when I walk around in my socks—

which I can’t do for long

because it’s so cold that my scalp tightens.

Halfway up the stairs is a stained-glass window

with a picture of flowers and butterflies in a garden,

like spring.

Papa opens the cellar door and flips the light switch.

I peer down the dark, dusty staircase.

And in the kitchen sink are the bowl and spoon Papa used for his cornflakes this morning.

He shows Mama the cinnamon-colored dishwasher built under the counter

and the garbage disposal built into the sink.

These are firsts for Mama.

She opens the dishwasher door and pulls out the top rack.

“Hmm,” she says, and that’s all.

Papa and I look at each other.

We know we’ll find out what that means,

but it won’t be now.

“This is our room,” Papa says,

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things