- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

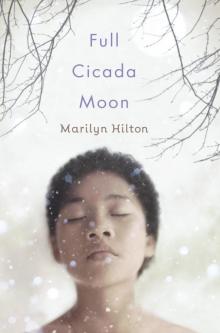

Full Cicada Moon Page 9

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 9

“Sit with us,” they say,

and smile.

That’s when I stop laughing

and almost tell them the truth.

That’s when I wish I could tell them

how much it hurts and how lonely I feel—

which is why I just taught them a word

my mom would be ashamed to know

that I know.

Party Snacks

Next Friday is the last day of school, so

Mr. Pease is holding up a sheet of paper

in homeroom. “Quiet down, students.

Please sign-up for our end-of-the year party.

You can bring any kind of snack,

like brownies or potato chips.”

He gives the paper to Robert

in the first seat in the first row.

When it comes around to me,

I write Sushi, even though I haven’t asked Mama

if she’ll make it.

Then I look at what I’ve written

and think of the faces

the kids will make when they see the sushi

and the tone of their voices

when they ask, “You eat raw fish?”

even though that sushi would have cooked shrimp

and eggs

and vegetables,

or maybe hot dogs.

So I cross out Sushi

and write Chocolate chip cookies.

The End of the Beginning

It’s the last day of school.

The last day of my seventh grade.

And the last class of my last day

of seventh grade

is English.

Mr. Pease is handing back our journals.

When he gives me mine,

he holds it a second longer,

and says, “Very good, Miss Oliver.”

I open it

and flip through the pages.

Mr. Pease wrote things like Very good

and Very observant

and Really?

And he marked spelling mistakes.

I skip past the pages

where I know I’ve said things

that weren’t kind or respectful

about other people.

But when I get to the last page,

I see a big, red A+

and next to that:

I enjoyed reading this very much

and I do know you better.

Please keep writing poetry—

you have a gift.

I’m glad it has helped Mr. Pease know me.

But even better,

it has helped me know myself.

Summer

1969

The Question

Papa’s last class ended today,

and college is over for the year, too.

We’re eating supper on the picnic table in the backyard

because the air is warm and soft

as the sky turns colors.

The quarter moon is a shell on the sunset’s shore.

Papa puts down his fork

and leans his elbows on the table.

I slap a mosquito on my arm

and wait for him to talk.

“We have a decision to make,” he says.

“I’ve been here for two semesters,

and you and Mama have been here almost six months.

If it’s not working out for you, we can leave.

Someone offered me another teaching position today, in Texas.”

“Does that mean we’ll have to move again?” I ask.

“Yes,” Papa says.

Mama stays quiet.

“Do we have to make up our minds now?”

“I’ll need to know by the end of July

at the latest,” Papa says. “And the question is:

Do we stay or do we go?”

Pie, the Moon, and Stacey

Today is Flag Day,

and Mama hung a flag on the front porch.

It curled in the breeze like a cat’s tail.

Today is also my birthday.

We had lemon meringue pie

instead of cake because that’s my favorite,

and Neapolitan ice cream,

because I can never decide which flavor I like best.

Papa turned on the sprinkler,

and Stacey and I did ballet leaps and bunny hops

through the spray.

Then Mama and Papa gave me a hi-fi record player,

and Stacey gave me the new Temptations album.

I asked them if they had planned it that way,

and everyone laughed and looked away

so I knew the answer was yes. It made me happy

that they had talked behind my back

in a nice way.

Then Timothy came over with a present.

He glanced at Papa and handed me a little box

with COTTLE’S written on the lid.

Inside was a happy silver moon on a chain.

Stacey is staying over tonight.

It’s my first sleepover

since Shelley and Sharon and I slept on their living room floor

and watched The Flying Nun and Bewitched

the night before Mama and I left Berkeley.

Stacey and I are sitting at the two window seats

and talking through the screens. We can hear each other

inside and out.

“Just think,” she says,

“you’ve been on this earth thirteen years.”

I look up at the sky and wish

new moons had names, like full moons do.

I will call tonight’s moon New Birthday Moon.

When I opened the box from Timothy today,

he said, “Look—I found your moon.”

I am thirteen today,

and the moon that disappeared

from my science project

and from tonight’s sky

is here, dangling at my throat.

Magicicadas

Because of the New Birthday Moon tonight,

the stars are full twinkling brilliance.

Later, after the mosquitoes have disappeared,

Stacey and I will go outside and twirl.

“Why did they name you Stacey?” I ask through the screen.

“Mother said a nurse named Stacey helped her

after I was born,” she says. “I was a preemie,

and Mother and Daddy thought I was going to die.”

“But you didn’t, thank goodness,” I say.

“I’m too tough. When I get old,

and am about to go, I’ll kick death so hard

that it will go away.”

That’s another reason I like Stacey.

“How did you get your name?” she asks.

“My dad said that when I was born,

Mama thought I cried like the cicadas’ song—

mee-mee—

and made her think of home. Japan.”

“We have cicadas in Georgia.

I love the sound. It’s a summer sound,”

she says softly, like she misses them, too.

Then I say, “I read there are cicadas

that live in the ground for years.

They’re called magicicadas,

and when they’re ready, they all burst out at once

and fly, blocking out the moon.”

“Mother saw that once,” she says. “I wish we could see them here.”

I look into the part of the sky

where the New Birthday Moon should be,

and say, “They wait until just the right time.�

��

Apollo 11

Timothy comes to our house at nine o’clock this morning

to watch the launch of Apollo 11,

which will carry three men to the moon.

Papa says if we don’t see this historic event,

we will regret it the rest of our lives

because he’ll never speak to us again.

But he doesn’t have to tell me that,

even if it is a joke.

Mama brings me a tube of butcher paper,

which I unroll on the living room floor

to make a map of this historic event.

I draw Earth

and the Saturn V rocket steaming on the launchpad.

I draw a window near the top,

and Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Mike Collins

waving.

“One day that will be me,” I say,

and Timothy and Papa say, “May-be.”

Mama says, “Just be careful.”

Then I draw the moon

two hundred thousand miles away from Earth.

“Good luck and Godspeed,” says the control tower

to the astronauts,

and Neil Armstrong answers, “We know it will be a good flight.”

The countdown begins,

and the numbers on the TV change every second—

as my heart pounds for the astronauts—

“. . . five . . . four . . . ignition sequencing starts . . . two . . . one . . .

zero.”

Fire and smoke billow from the launchpad

and Saturn V leaves the ground.

“Liftoff. We have a liftoff.”

The flaming fuel putters, pushing Saturn V higher

and higher in the sky, through the clouds.

I feel power, speed, and the drag of gravity.

The rocket looks like it’s traveling sideways.

The boosters break away,

and now the ship becomes a bird with fanlike wings,

now a faint dot.

“You’re looking good,” says Houston.

Timothy and I pick up each end of the butcher paper

and carry it up to my room.

We tape it on the long wall.

I draw a dotted line for the flight path,

from Earth to the moon

and back—

for the eight days the astronauts will be in space.

And I draw a solid line for their trip so far.

I will draw them

all the way home.

Room of Kings

In Papa’s study

a picture of Jesus hangs on the wall,

so when the sun rises in the morning

his blue eyes sparkle.

Across the room is a picture of President Kennedy.

He looks straight into the camera

with one stern eye

and the other eye trying not to smile.

Next to him is a new frame,

with five black-and-white pictures, each in its own pane:

The Reflecting Pool’s walkways teeming with

people

Signs for We Demand Equal Rights Now!

Papa with two friends, looking young and

dorky

Dr. King raising his arm above the crowd

“Did you go to the march?” I ask, peering at Dr. King,

who might have been saying “Let freedom ring!” at that moment.

“It was incredible, and it was a safer thing to do.”

His heart was in Birmingham and Selma, he adds,

but he had a wife and a little girl,

and was studying for his PhD.

“Safe is a cop-out, but I had to think of you and Mama

and my own dreams.”

So he and his friends drove from Berkeley to Washington

without stopping.

They ate food that Mama had packed,

and switched drivers every six hours.

“This is big, big country, Mimi,” he says,

like he forgot how Mama and I came to Vermont.

Then he tells me the air on that August day

felt thick with heat and determination

smelled like baby powder, Old Spice, and grit,

sounded like clapping and harmony, a

million footsteps on the same path

tasted like hot dogs and hope.

Papa opens his desk drawer and takes out a button—

March for Freedom and Jobs—

and tapes it onto the new frame. He says,

“Even now, that day reminds me

that raindrops are stronger than hammers.”

Remember This Night

The Sea of Tranquility slides under the window of Eagle, the lunar module.

The moon’s surface gets closer, bigger,

and Eagle lands.

We wait

to see a man walk on the moon

for the very first time,

ever.

Mama serves us potato salad and rolled-up ham slices

on TV trays

while we watch the fuzzy black-and-white pictures

from so far away.

She brings me a Coke with ice

so I can stay awake

to see the first man walk on the moon.

But I don’t need caffeine to stay awake tonight.

Papa says, “Remember this night.”

Mama says, “To tell your children,

my grandchildren.”

It’s almost eleven o’clock

and Eagle’s hatch is open.

I stare at the TV

as Mama passes the bowl of popcorn.

Neil Armstrong stands on the ladder,

which he says is sunk one to two inches into the moon’s surface.

Then he steps into the dust

and touches a brand- new world.

He says,

“One small step for man

One giant leap for mankind.”

Papa says, “Those words just traveled around the world.”

Soon, Buzz Aldrin squeezes out of the lunar module

like a person being born all over again,

and the two astronauts hop around

like moon kangaroos.

“It has a stark beauty all its own,” Neil Armstrong says,

“like the high desert of the United States.”

The lunar surface does look beautiful, but

I wonder if he has ever seen

winter in Vermont.

The Real Thing

The astronauts have returned to the lunar module

and are sealed inside.

Watching them on TV was one thing,

but not the real thing,

so I go to the backyard

to look at the moon in the sky,

which tonight is waxing crescent, almost

first quarter,

showing the shore of the tranquil sea,

where the astronauts are resting in Eagle.

In the silence of this magical night,

low voices drift from Mr. Dell’s yard

and dark figures move in the pale light.

When my eyes adjust,

Mr. Dell and Timothy are huddled over the telescope.

My heart thuds—

they’re watching the moon through the telescope.

Can they see

the lunar module gleaming in the sea,

the flag planted in the dust,

Columbia orbiting the moon, waiting to rendezvous?

Timothy moves away from the telescope.

I flap my arms to catch his eye,

and he waves behind his uncle’s back,

then points to the moon.

I wave back and point and smile.

Pattress sees me and runs to the fence

and barks hello.

Mr. Dell steps back from the telescope,

straightens up and sees me.

“Get back!” he barks

at Pattress,

at me.

My heart hurts

over Pattress,

Timothy,

the telescope.

Papa said to remember this night.

But he doesn’t have to worry, because

I will never forget it.

The Answer

It’s time to decide

whether we will stay in Vermont

or move to Texas.

Papa has called Mama and me to the picnic table

to take a vote. The air smells like ozone from the rain,

and the Full Buck Moon glows through a veil

of clouds.

“What do you say, Emiko?” Papa asks.

“Up to you,” Mama says.

“Not this time,” Papa says. “It’s up to all of us.”

Then he touches my arm.

I knew this moment was coming.

I don’t want to go to Texas.

I don’t want to stay here either.

I want to go back to Berkeley

and be with my cousins. But I have a feeling

my cousins wouldn’t be the same,

and everything would be different,

because I’m different now. I have changed in Vermont.

Papa’s waiting for my answer.

Didn’t he say to remember the past

but keep looking forward?

If we leave Vermont now, I’d never know

what it held for me.

I want to find out, so I vote

“Stay.”

“Now, Emi,” he says to Mama.

She looks at me and then at Papa

and says, “Stay, too.”

Papa rubs his hands together,

almost clapping. “It’s unanimous,” he says.

“Good things are in store for us here—

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things