- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

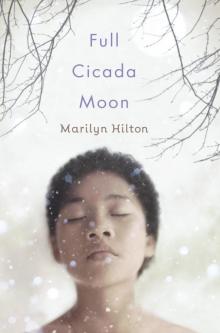

Full Cicada Moon Page 7

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 7

He looks down and shakes his head no. “But I don’t care.”

After Timothy leaves, I realize he didn’t ask me

all the usual questions.

Maybe he doesn’t care about them.

And that makes me smile.

Inheritance

While Mama is at the wives’ tea,

Papa and I are baking bread.

He uncovers the dough that’s been rising in the ceramic bowl

his dad—my grandpa—made long ago.

“And this bread is from your grandma’s starter,” Papa says.

It has lasted all these years,

longer than I am old.

“Tell me her stories,” I say,

even though I’ve heard them all before.

As Papa spreads flour on the counter and kneads the dough,

he tells me how she walked to the fields every morning in summer

to work the crops,

and ate lunch from a tin pail,

and visited with neighbors on their front porches when the day was done.

At school she shared a desk and a pencil

and wrote double between the lines to save paper.

He tells me how it feels to hold your breath

in an outhouse,

and I wonder if these are her stories

or his.

I hold my breath and pretend I’m there,

forgetting for a moment I’m in this warm kitchen

making bread with my dad.

Papa pinches off a handful of dough

and replaces it tightly in the jar.

This is our history, and I won’t forget it.

Then he writes my name in the flour:

Mimi for the cicada’s song;

Yoshiko for my obaasan;

Oliver for Papa.

“You have your mama’s eyes,” he says,

“and you have my stories.”

April Moon

Timothy raps on the back door.

His cheeks are flushed in patches,

and his brown eyes sparkle.

“If you want to see the telescope,

you gotta come right now.”

I pull him inside so he won’t freeze

while I put on my shoes and jacket.

The kitchen smells like warm bread,

and he sniffs. “Mmm,” he says,

and I tell him, “My dad’s baking today.”

“Your dad? That’s cool.

All set?”

We run to Mr. Dell’s garage, careful

not to slip in the muddy patches in our yards.

Timothy slides the heavy door shut behind us.

He leads me to the back of the garage,

past all Mr. Dell’s machines,

where the windows are as tall as the ceiling

and curved at the top.

Planted near the windows is the telescope

pointed toward the sky,

like a kid gazing at the stars

in wonder.

Timothy bends over and looks in the eyepiece,

turns a knob, turns it some more,

then waves me to him.

“Can I?” I ask, the words shaking in my throat.

“You can look through it,” he says,

“but do not touch it.”

I clasp my hands behind me,

just to show him I will not touch it,

and bend over the eyepiece

and look

at nothing

but blue sky.

“Be patient,” Timothy says.

So I look again and wait,

for something to come into view.

And it does—

at first I see an edge so bright I have to blink,

and curved like the peel of an onion—

the moon, so close.

It’s peering back at me

as it slides across the circle of lens,

a waxing crescent

dark,

silent,

enormous.

I see its pockmarks—

its craters and seas—

though it tries hard to hide them

in our shadow.

“I will touch you,” I whisper,

but Timothy says, “I said no touching.”

His words pull me back

to Earth.

Hope

All I saw when we came into this garage

was the telescope.

But now that the moon show is over,

I smell sawdust—

and turn around

to see a workbench

and power tools.

Could they be the other way to solve my problem?

“Does your uncle let you use those tools?” I ask Timothy.

“Yeah, but mostly to fix things.”

“Do you think I could I use them?” I ask,

and tell him about my science project.

He doesn’t say

girls aren’t allowed,

tools are dangerous,

you don’t have any training,

it’s impossible.

What he says is, “I’ll show you how.

But only when he goes out.”

There’s a dark, enormous silence

between us. Finally I ask,

“Why doesn’t your uncle like me? Why doesn’t he

like my family? It’s because

we’re not like him, right?”

Then I wish I hadn’t said that to Timothy,

my only friend besides Stacey,

in case he hadn’t noticed we look different

and now he will see

and change his mind about me.

But I should have known better. I can trust Timothy,

because he shakes his head and says,

“He doesn’t like anybody.

I don’t know why, but

most of all, he doesn’t like

himself.”

Secrets

I don’t want to keep secrets

from my parents, but since Mama hasn’t asked

where I go with Timothy every morning

and why,

I’m not keeping a secret,

not really.

Every morning of vacation,

Timothy has knocked at the back door

after his uncle has left.

We go to the garage, and he shows me

how to use the tools for the next step

of my moon box.

Then I do each next step.

He’s teaching me how to saw wood

and hammer and sand,

and reminds me, “Put on your goggles.”

It’s not cheating because I am doing all the work.

When we hear Mr. Dell’s truck chugging up the driveway,

we hide my project

behind a stack of tires in the garage,

and I sneak out the back door.

Each day when I go home,

Mama asks, “Did you have a nice time with Timothy?”

And I say yes, because it’s the truth.

But I still feel like I’m

keeping secrets.

Weirdos

Today in the garage,

Timothy asks, “Remember when your father was baking bread?”

I’m measuring a board and nod

instead of saying yes,

so I won’t have to start over.

Then I mark the length with a pencil and ask, “Why?”

“Well . . . do you think he would teach me?”

“You want to make bread?�

��

Timothy looks down

and brushes the board. “I want to learn to cook.

Do you think that’s . . . weird?”

“I like to hammer and saw. Do you think that’s weird?”

“No,” he says, looking at me. “It’s cool.”

“Well, I think my dad would like to teach you. And

that would make us even.”

“But I like showing you how to do this. I like

being around you. I mean,

I like you.”

I’m glad the pencil rolls off the board just now,

so I have another reason to look down.

Sea of Tranquility

It’s Thursday night, and Timothy and I

are more than halfway through April vacation

in different schools.

The moon box is almost done—

today we sanded it

then hid it, like always, behind the tires.

Tomorrow I’ll bring it home and paint it black.

Tonight, Papa is showing Timothy

how to make a basic loaf of bread.

It’s going to be round

because Papa says that’s easiest,

and this is Timothy’s first loaf.

While Timothy is learning how to bake,

I’m making a papier-mâché moon

by gluing newspaper strips to a ball

that Papa found in the cellar.

The hardest part will be shaping the craters and seas

so they’re accurate.

But that part will also be the most fun

because I like their names,

which sound like poetry:

Sea of Tranquility

Kepler Crater

Sea of Vapors

Grimaldi Crater

Ocean of Storms, and

Lake of Dreams

are my favorites.

When the moon dries

I’ll paint it white and different shades of gray

and hang it in the moon box.

My project will be like science meets art,

and it will win first prize.

Timothy slides the bread pan into the oven

and shuts the door.

His cheeks are flushed, like when he’s cold or embarrassed,

but tonight I think it’s how his happiness is showing.

“Thanks, Mr. Oliver,” he tells Papa.

“Can we make something else . . .

tomorrow? I have to go back to New York on Saturday.”

Papa smiles. “I’ll show you how to make an omelet.

It will come in handy when you go to college.”

“Okay, but that’s a long time away,” Timothy says,

and Papa says, “Not really.”

The bread will take an hour to bake. I hope

Timothy will want to stay until it’s done,

instead of going out and coming back.

When he sits at the table and asks

how my moon is coming along,

I feel my cheeks flush.

Sign of Spring

I call it fireworks exploding yellow.

Papa calls it forsythia.

Mama just says “Achoo!”

Water and Dirt

Timothy and I are at the workbench

in Mr. Dell’s garage.

A thread of spring weaves through the air.

Even though it’s still April,

I get a whiff of May in Vermont—

light, sweet, and happy.

“Wesley’s thinking of joining up,”

he says as we rub the moon box,

feeling for rough patches that need more sanding.

“He got a low draft number

and figures he’s better off enlisting.

Then he’ll be able to choose the branch.”

I guess “Marines?” and he nods.

“My dad was a Marine.

He met my mom when he was stationed in Tokyo.”

I can tell by the way Timothy concentrates on the box

that he doesn’t want to hear how my parents met.

He says, “I don’t want him to go to Vietnam.”

I feel sandwiched by wars

and don’t know what to say to Timothy, except,

“Are you coming back here this summer?”

“Probably. Hope so,” he says.

I hope so, too,

and tell him that.

“This looks good,” he says

about my moon box. “You did a good job.”

“Can you help me carry it back?” I ask.

He opens the garage door—

and Mr. Dell walks in, blocking our way out.

“What you got there, Tim,

and who’s that with you?” he asks.

I look at Timothy, who’s flushed

now with embarrassment

or fear. He’s not talking, so I answer.

“It’s my science project,

and Timothy showed me how to put it together.”

“He did,

did he?” Mr. Dell says.

“Yeah, Uncle Raymond.”

“Well, now, you didn’t happen to use my tools to put it together,

did you? Because wouldn’t that be cheating?”

“I don’t think so,” Timothy says.

“Oh, I think so. Especially when you’re not supposed to see this girl.

And now she’s in my garage.”

Mr. Dell looks at me with eyes colder than February.

I decide

I’m not as much afraid of him

as I don’t like him.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Dell,” I say,

so respectfully that Papa might be proud.

“I can carry it by myself, Timothy.”

“I think you should,” Mr. Dell says,

and steps away from the door.

I squeeze myself and the moon box through.

It’s too bad we haven’t painted it yet

because my tears are soaking into the lid

as I walk home through the mud.

I keep hearing Mr. Dell’s words

and stop to catch my breath

when I realize

Timothy won’t be coming over tonight

to make omelets.

One-Way

Why do all my friends here—

Stacey and Timothy—

come to my house

but never invite me to theirs?

Mama’s Visitor

Mama met someone named Dr. Haseda

at the wives’ tea.

(I wondered if she was the someone Papa talked about.)

This afternoon Dr. Haseda came to our house

and brought lemon cookies as an omiyage.

Mama set them out in a pretty dish

and made a pot of tea.

Dr. Haseda was born in Los Angeles

and went to college in New York,

where she met her husband.

She teaches Japanese at the college.

Today she brought her daughter, Kate,

who is one year old.

At first, Mama called her Baby Cake

and soon we were all calling her that—

even Baby Cake, who can already say ten words.

Even though Mama said she only needs Papa and me

and the turkeys,

I’m glad she has a new friend,

because maybe then she will start to feel at home.

After we walked them to their car

and waited until they drove away, out of sight,

I said, “It

was nice of her to visit you.”

Mama smoothed her hair and said, “Papa asked her.”

“Are you mad at him for that?” I asked, confused.

“No, Mimi-chan. That is love.”

Spatial Reasoning

“This is a mistake,”

says Mrs. Golden, my guidance counselor.

She slides her glasses onto her nose

without taking her eyes from the test results in her lap.

“This is your score on spatial reasoning.”

Her fingernail points to

95 out of 100.

A mistake?

“Girls never score high on this test.”

She takes off her glasses,

looks,

says nothing,

and waits for me to explain why

a girl

like me

would score as high as a boy

like, say, Andrew Dutton.

Does she think I cheated?

They showed you the pieces of something

taken apart

and you had to choose the way it would look

all put back together.

“I liked that test,

and it was easy.”

“Something went wrong,

and you’ll have to take it again.”

Mrs. Golden shakes her head

and puts her glasses back on,

and I know the subject is closed.

Looking Forward

“While you’re here,” says Mrs. Golden,

“let’s talk about your schedule for next year.

You’ll be in eighth grade,

your last year before high school.”

She pulls my schedule from the same manila folder

and puts it in my lap.

I skim the list while she reads:

English

Math (Not algebra)

US History—Civil War to Present

Art

Music

Physical Science—Intro

Home Economics

Gym

Clubs (optional)

“Do you have any questions?” she asks.

“Can I change my schedule?”

Her eyes narrow. “What do you want to change?”

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things