- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

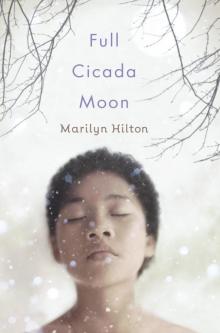

Full Cicada Moon Page 3

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 3

“Whatever you want.”

I raise my hand again, and he says, smiling, “You still have the floor.”

“What kind of writing can we do?”

He leans forward. “Whatever you want, as long as I can read it.

Experiment, try something new.”

“Like poetry?” someone asks.

“As long as I can read it.”

I know

exactly what I will write in my journal for Mr. Pease,

and by June, he’ll understand better

who I am.

Notions

“This spring, you’re going to make aprons,”

says Mrs. Olson in home ec.

“And next fall, you’ll wear them when you cook.”

“Why don’t we just buy an apron?” someone asks.

I had the same question,

because Mama has plenty of aprons that I can wear

and I’d rather make a skirt.

“Because you’re learning how to sew,” Mrs. Olson says,

passing out a paper with Notions printed at the top

and a picture of the apron—

a rectangle with a pocket and a long strip for the tie.

It looks simple and plain.

If Mama designed this apron, it would be a lot fancier.

“What are notions?” someone asks.

“They’re your thread and your needles and pins.

You can get everything in town.”

I have a notion that Mama and I

will go downtown this Saturday.

I have a notion that she’ll buy one fabric

with flowers for the bottom part

and another fabric with stripes

for the tie and pocket.

Then she will buy extra fabric for a ruffle

and rickrack for a trim.

And I have notion

that if I sew this apron very fast,

I’ll have time to make a skirt.

Science Class

The last class of my first day

is science.

My teacher, Mrs. Stanton, has curly hair

like mine, but hers is light-brown-turning-silver.

She wears a forest green skirt that flares,

a beige turtleneck,

and a cardigan buttoned at the top like a cape.

Her glasses are on a chain.

“It will be May before we know it,”

she says, leaning against her desk,

“and time for the Science Groove.”

She waits—for the kids to say something

or clap, but all they do is lean on their arms

or doodle, or yawn and stick out their legs.

They all know what she’s talking about. But I don’t.

I want to ask what the Groove part is all about.

My arm aches to rise. But,

since I already feel like Mama’s maneki-neko,

I wait

for someone else to ask.

“I’ll help you choose a project,” Mrs. Stanton says.

“You’ll write a report and do a presentation for ten minutes.

And, it must be entirely your own work.

No one can do it for you.”

Now my hand springs up.

Mrs. Stanton nods. “Wait till I finish,

then you might not have a question anymore.

Everyone will set up their projects in the gym

and the projects will be judged.

The best projects will win awards.

Did that answer your question, Miss Oliver?”

“Yes, thank you.”

Here they call it a Groove. In Berkeley

we called it a Fair. I won third prize at the Fair.

At the Groove, I will win first.

Little Lies

After school

Papa is waiting near the buses.

He stands like a giant sequoia,

wearing his tweed coat that Mama made

and his mustache and those glasses—

all he needs is a pipe.

He nods hello

to the kids

who crane their necks to stare

as they pass.

Some ask “Who’s that?” and

some glance at me,

guessing the connection.

“How was your first day?” Papa asks,

adjusting my scarf.

I know he wants me to like Hillsborough,

so I shrug and say, “Good.”

There was some good, like the Science Groove

and writing in a journal.

“Are we going home now?

Where’s the car?”

“I left it at the college,” he says. “We’ll walk there

so you can see the downtown.

Do you have everything—books

for homework, your lunch box?”

“Yes,” I say quickly,

telling the truth about the first part.

I have my books. But my obento

is still in my locker.

Downtown

We head down the street to town—

Papa striding and I with quick, short steps

so I don’t slip and crack my head open,

which is Mama’s biggest fear.

Everything is white and black and gray

and slush.

Except for the sky, which is . . . sky blue . . . and alive

with sunlight and snow rainbows.

We walk past a lawyer’s office, a barbershop,

the Hillsborough Savings Bank, and a drugstore,

where I see toys and a soda fountain

through the frosted window.

Somewhere, a shovel scrapes cement.

We pass—

A round woman

in a gray coat with big buttons that look like

mine

and a plaid scarf over her mouth.

She carries a grocery bag

and wipes her eyes with a tissue.

A boy in a blue parka with the hood string pulled so tight

his face is a thumb,

and mittens pinned to his cuffs.

A college girl in a long skirt made out of

jeans

and a short, red sweater.

Her hair bounces around her shoulders as

she walks.

Each one stares at us until we get close

and then they look away.

Papa says, “Hello,”

and gives a little nod.

Round woman nods back

and clutches her grocery bag.

Boy backs up to a signpost

and twists around it as we pass

to stare.

College girl just keeps on walking,

as if she doesn’t see us.

As if she didn’t hear

my gentle dad’s hello.

Farmer Dell

Our neighbor’s house,

where I saw Pattress and the boy,

is long and low, and snuggled into the snow.

There’s also a garage that’s twice as high as the house.

Old cars and trucks and propane tanks

lie around the yard like lazy farm animals.

A mailbox sits on a post at the end of the driveway,

with DELL stenciled in white letters. Whenever I see it,

I sing “The Farmer in the Dell” in my head.

The man who lives there doesn’t look like a farmer,

and I never see a wife or a cow, but I call him

Farmer Dell.

Farmer Dell always wears the same thing—

green work pants, a plaid wool jacket buttoned to his neck,

and work boots. If it’s really cold, he wears a red-checkered hat

with the flaps over his ears.

Pattress is always with him,

and sometimes when Papa and I drive to school,

she’s sitting at the garage door.

But I haven’t seen that boy again.

Sometimes Farmer Dell is driving a backhoe,

clearing snow in the yard. In the afternoon

another car or truck will be lying in the nest he made.

Sometimes he’s walking to his mailbox

or standing beside it.

And sometimes he’s pushing a snowblower

down his driveway.

The snow cascades into a perfect trim,

like piping on a birthday cake.

Every time we pass by our neighbor,

Papa waves to him.

But no matter what Farmer Dell is doing,

he never waves back.

Each time he doesn’t wave back,

my mouth goes dry.

This morning, I ask, “Why?”

Papa says, “Maybe he can’t see very well.

Or maybe he doesn’t like us.”

That is why my mouth goes dry.

“But he doesn’t even know us.”

Papa shifts his hands on the steering wheel. “You’re right, Meems—

he doesn’t . . . yet.”

And then the spit comes back into my mouth

because even if Mr. Dell doesn’t like us,

Papa said the words,

so they don’t scare me as much.

Outside the car, light and dark and gray all stream by,

and I think, Drip, drip, drip.

Others

In Berkeley we lived in a two-bedroom house

next to my second cousins, Shelley and Sharon,

and Auntie Sachiko (who’s really Mama’s cousin)

and Uncle Kiyoshi.

There was no fence between our backyards,

so it was like we all lived in the same house.

Auntie let us live there

while Papa finished his schoolwork,

as long as

he did repairs on their apartment building

and Mama told people he was Italian.

Shelley and Sharon have Japanese middle names

like me: Akiko and Tomiko.

Sometimes they speak Japanese to Auntie and Uncle

and to each other,

and sometimes they combine English and Japanese.

My cousins taught me the Japanese words

that Mama would never say.

Sometimes we pretended we were Southern belles

who could speak Japanese—

“Ohayo gozaimasu, y’all.”—

which made Mama and Auntie cry-laugh

out of breath.

Papa wants us to speak only English,

not because he doesn’t like Japan

but because he says people get scared

when they hear a different language.

My cousins were my best friends.

We had other friends

whose parents or grandparents came from Japan

or China, Korea or India, Ghana or Germany or Mexico.

We all understood our families’ languages

and ate the foods of their countries.

It was like we were all in the Other check box,

having in common

speaking English,

being American,

and feeling that we didn’t belong either in our parents’ worlds

or in this one.

But I am not Other;

I am

half my Japanese mother,

half my Black father,

and all me.

Winter

Quiet

sounds like winter in Vermont:

Snow taps the bare trees

Flames sing in the fireplace

Mama’s slippers scuff the floors

The teakettle applauds to a boil

Hot water pours into a cup

A sip—

And Papa’s “Quiet, please. I’m grading papers.”

Karen and Kim

The two girls carry their trays to my table,

pocketbooks swinging from their elbows,

and sit on either side of me.

I didn’t even need to invite them.

“We want to get to know you.

I’m Kim, I’m Karen,” they say.

“You lived in California?” Karen asks.

I nod. “Uh-huh, in Berkeley.”

“Did you go to wild parties there?”

“Did you surf?”

“How many movie stars did you

meet?”

“Did you go to Disneyland

every weekend?”

I laugh and sip some milk.

“No. No. No. No,” I say. “I didn’t live in Hollywood.

I lived up north, near my mom’s cousins.”

“Can I touch your hair?” Kim asks.

It’s a strange thing to ask, but I lean toward her.

She smooths the top of my head and runs her hand down my braid.

Then Karen takes a turn, and says, “It’s so curly.”

Mama likes my hair pulled back tight and neat,

but a few curls always escape.

“I wish my hair was curly like yours,” says Karen,

whose hair is straight and long and blond,

and I don’t believe her.

“What nationality are you?”

I try not to sigh. “My dad is Black and my mom is Japanese.”

“Japanese-Japanese, or was she born here?”

“Japan. Hiroshima.”

“Didn’t we bomb Hiroshima?”

“Yes.” And the radiation is ticking in Mama’s bones.

“Do you know any Japanese words?” Kim asks.

“Sukoshi dake,” I say,

and they look puzzled. “It means ‘Just a little.’

My dad doesn’t want us talking Japanese.”

“What does he do to you if you talk

Japanese?”

“What? Nothing.”

“I mean, I just thought . . .” Karen looks at

Kim.

My neck is prickling.

“Do you get a tan?”

I look at my arm. “Well, I get browner in the summer.”

“But not your palms, right? They still look like ours.”

Kim shows her hands to compare.

My lunch is done,

and so am I

with Karen and Kim.

Cooties

The first thing I notice about Stacey LaVoie

is her feet. We’re standing in the corridor outside the gym

and she’s wearing red tights—and not the textured kind.

Even I know that you stop wearing red tights after fifth grade.

But I like that Stacey wears them anyway,

and that her big white toe sticks out of a hole

like a marshmallow.

She tries to cover the toe with her other foot,

but I’ve already seen it.

The next thing I notice is that black eyeliner

circles her whole eye

and ends with a little wing,

and she has pierced ears (Mama would never let me),

and earrings that dangle

just short of disobeying the dress code.

Miss Bonne, our gym teacher, is weighing us.

We are lined up in our stock

ing feet

outside the locker room.

Miss Bonne holds a clipboard in her hand

and a pencil in her mouth

while she slides the weights up and down the scale,

nudging them, zeroing in on the target.

“Next!” she calls.

“Watch out for the cootie hole,” says the girl next to Stacey

as we move up another person-space in line.

“The wha-at?” Stacey asks,

sounding like my cousins talking Southern,

only Stacey sounds real.

The girl points to a little hole in the wall

near Stacey’s waist. “Don’t touch it, or you’ll get cooties.”

Stacey nods, making her dark hair bounce

like a girl in a Breck shampoo ad.

“I don’t know what she’s talking about,” she whispers

to me. “Do you?”

“I think they’re invisible bugs that you can catch.”

The thought of cooties running all over me

makes me shiver, even if they’re made up.

“Sounds kinda stupid,” she says,

and I agree.

“Next!”

We move up, and now I’m next to the cootie hole.

Cooties are stupid, but I move away from the wall anyway.

“I was new in September,” Stacey says.

“We came from Georgia. My daddy teaches at the college.”

“Mine, too,” I say, feeling happy

that we’re both new

and both professors’ daughters.

“It sure is different here, huh?” she says,

and shifts her weight to her other foot.

But she loses her balance

and falls onto me,

and I fall onto the next girl,

and on down the line.

“Stop pushing!” someone says,

shoving the girl who just knocked into her,

and the ripple swells up the line,

growing in strength and force

and intent.

When it comes back to me, I stop it

by falling into the wall,

against the cootie hole.

“Cooties!” the girl beside me says, and jumps away.

“I don’t want to catch them!”

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things