- Home

- Marilyn Hilton

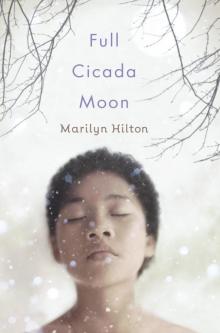

Full Cicada Moon Page 16

Full Cicada Moon Read online

Page 16

Happy New Year!”

Inside is a brand-new five-dollar bill

that smells like fresh ink

and feels like a new leaf.

Then Papa comes into the kitchen

and says, “Happy New Year!”

And one by one, everyone wakes up

and says, “Happy New Year!”

Then no one says anything, and Mama

is looking like Mifune.

Papa whispers to me, “No man has come to the house.”

“Oh, that’s right,” I say.

She pours warm sake into a shallow cup and gives it to Papa.

He raises the cup, in thanks for a good year, and drinks.

Then he pours some for Uncle

and then for Mama

and then for Auntie.

Shelley and Sharon and I have some, too.

When I sip, the sake prickles my throat

and warms me all the way to my forehead.

We giggle

and after one sip, we stack our cups

and ask for cocoa.

Then Mama brings the nengajo from the drawer,

and we open them one by one.

“Here’s one from Mr. Singh,” she says.

Mr. Singh shared an office with Papa at Berkeley.

“How did he know about these?”

“Word must get around,” Papa says.

Then Mama picks up another card. “Nani?” she says,

and hands it to Papa.

He reads it, then takes off his glasses,

and says, “Excuse me,” and leaves the room.

Mama shows me the card.

It’s from Aunt Eleanor,

Papa’s little sister,

and I think, It’s a step.

After Mama wipes her eyes,

I ask, “If Uncle Kiyoshi comes across the threshold,

does that count for good luck?”

“No. He’s family,” she says,

and her brow puckers again.

But as we’re cleaning the kitchen,

the doorbell rings. “I’ll get it,” I say.

“Maybe it’s a man!”

I open the door

and can’t believe who I see—

Mr. Dell.

And Timothy’s standing behind him

with a face that says

“Remember this day.”

Confessions

Mr. Dell pulls his checkered cap

off his head. “Are your parents home?”

“Y-yes. Come in,” I say.

Papa and Mama come out to greet them.

Mama’s wiping her hands on her apron.

“Happy New Year,” Papa says,

and shows them into the living room.

“My uncle has something to say,” Timothy says

after they sit down.

Mr. Dell lays his cap beside him

and runs his hand through his hair.

“Did you have breakfast?” Mama asks,

and Auntie comes in with a tray of coffee.

“Thank you, ma’am,” Mr. Dell says,

and then, “Please stay here, Mimi.”

I sit on the edge of the hassock,

so I can make a quick exit if I need to.

Mr. Dell takes a sip of coffee,

and then says, “When you pardoned those turkeys—

or when you found Pattress—

I knew I needed to say this. It has nagged me

and it won’t let go.”

Auntie comes in with orange juice for Timothy.

“I owe you an apology,” he says.

“For what?” Papa asks,

and Mr. Dell raises his hand.

“Good neighbors are hard to come by.

I’ve been a terrible neighbor. I’ve been a terrible . . . person.”

He squeezes one fist and then the other.

“I flew missions in the war—

over Tokyo, ma’am,” he says to Mama.

“I dropped bombs. It wasn’t hard

if I didn’t think about where they were going.

And, I’m sorry, but all these years I haven’t thought about

where they went. But then you folks moved in.”

“And we reminded you,” Papa says.

Mr. Dell looks away.

“So, even though I don’t deserve it,

I’m asking for your pardon.

Just like for those turkeys.”

Mama slips her hand up to her mouth

to cover a smile. I know what she’s thinking—

that Mr. Dell isn’t a turkey—

because it’s what I’m thinking, too.

Instead, she says, “Don’t worry, Mr. Dell.

We will all be good neighbors now.”

Mr. Dell takes his cap and stands to leave.

“I just wanted you to understand,

and I hope one day you will forgive me.”

Mama says, “You are pardoned.”

After Mr. Dell shakes Papa’s hand,

he looks at me with a little nod.

I’m not afraid of him anymore—

in fact, I like him,

because now I know what’s underneath his crust.

I might never have this chance again,

so I say, “Thank you for the present.”

Mr. Dell frowns like he’s trying to remember

and says, “I don’t know what you mean.”

Then he and Timothy leave,

and Mama and Papa and I go down the walk with them,

saying “Watch your step” and “It’s cold out here,”

and wait until our neighbors go back home.

Then I say, “That was weird,”

but Mama says, “That is love.”

Vermont Neighbors

I used to think the people of Vermont

were like the snow—

crusty,

chilly,

and slow to thaw.

But now I think

they’re what’s underneath.

Like the crocus bulbs making flowers all winter

in the dark earth—

invisible until they push through the snow—

and like the cicadas growing

underground for years—

until they burst from the ground—

the people of Vermont

do their hardest thinking

and their richest feeling

deep inside,

so no one can see.

Full House

A few hours later,

Baby Cake comes with her mom and dad.

She toddles into the house, and says,

“omedeto,” in her baby way.

Mama hands her an omochi ball

and then a money envelope,

which Dr. Haseda puts in her pocketbook right

away

so Kate won’t eat it.

Then Timothy comes back.

“It’s boring over there,” he says,

and soon Stacey comes with her parents.

The adults go into the living room

to watch the Rose Parade,

and the rest of us sit at the table

and play Go Fish and Old Maid and Crazy Eights

because we can’t play any card games in our house

that use money or have names like liquor.

“It’s too bad there aren’t any boys here,”

Sharon says, “or we could play Truth or Dare.”

“Excuse me,” Timothy says, sweeping his cards into his hand.

“You’re different—you’re Mimi’s friend,” she

says, and we all laugh.

Baby Cake is sitting in my lap.

She keeps grabbing my cards,

but I’d rather play Pat-a-Cake with her

and name her toes—

Piggy Wiggy

Penny Rudy

Rudy Whistle

Mary Hossle

I grasp her big toe

aaaannd

—Kate wiggles and squeals—

Big Tom Bumble!

Then I notice the TV sound is soft,

and Papa is talking very low.

All of us in the kitchen

whisper our game.

“Got a queen?” “Go fish.”

“I might be heading up a new program

in the fall,” Papa says. “African American studies.”

“That would be a great opportunity for you,”

Dr. Haseda says.

“Yes,” Papa says, and sighs. “And a lot of work.

But the administration sees a new decade ahead

with changes.”

“Congratulations, man,” Rick says,

to the clink of many glasses,

and Papa says, “So, we’ll be staying here for a while.”

And I hear more clinks.

In the kitchen Shelley says, “A toast

to your dad,” and we all lift our glasses

of ginger ale and Tab and root beer.

She clinks my glass

and says, “omedeto gozaimasu . . .

y’all!”

This Year and Last Year

We girls are sleeping in my room—

Shelley and Sharon and I in my bed

and Stacey in the rollaway.

Outside, the waning crescent

is just a peel of a moon.

“Do you sleep on the floor at home?” Stacey asks.

“No,” Sharon says, “but we can here.”

We all get out of bed

and put the mattresses on the floor.

“This is how to sleep Nihon-teki,” Shelley says.

“What did you dream about last night?” Stacey asks.

I had told her about hatsuyume.

Sharon says, “I had a bad dream—

a rat was chasing me around the house

and trying to bite me.”

“I hate those dreams,” Stacey says. “Then

I’m so happy to wake up.”

Shelley says, “Mine was a nightmare, too—

school started early and I didn’t have my homework.”

“I hate those dreams,” I say.

I wonder if my cousins are lying.

I wonder if they really had good dreams

but don’t want to tell them—

don’t want to let them go.

Then Stacey says, “I dreamed I was riding in a car

with Victor, and Mother was driving.

I wonder what that meant.”

“You’ll have to write and tell us,” Sharon says.

“What about Mimi’s dream?” she asks,

and they all turn to me.

I dreamed about flying again,

this time in a spaceship.

I will not let go of that dream,

so I say, “Hmm,

I didn’t dream last night.”

Then I close my eyes to the moon,

and the girls keep talking. Soon

their voices sound like snow against the windows.

I am drifting

to sleep,

eager

to fly again.

Adventure

Our cousins left this morning for the bus stop

early, as the sun painted the snow

in rose and flame.

We walked our family to the Malibu,

and after Papa got them settled in,

Mama handed Shelley a box

wrapped in a spring-colored furoshiki.

“You didn’t have to pack us a lunch,” Auntie Sachi said.

And Mama said, “It’s a long bus ride to the airport.”

“Bye-bye,” we said to our cousins, and waved

and bowed as Papa backed out of the driveway.

And even though Sharon and Shelley and I are a year older,

we made pig faces

until Mama and I could see only a tail of exhaust.

It’s what we’ll remember until we see them again.

Now our house, with only three of us,

feels twice as big as it did at sunrise.

It’s funny how people can take up so much room

in your heart

but you still have plenty left

for someone else.

Timothy knocks on the back door, his eyes wide,

and asks, “You up for an adventure?”

and Papa says, “Let’s be ready in five minutes,”

like he knows a secret.

Mr. Dell is waiting out front in his truck.

Mama and Papa sit in the backseat.

“Where are we going?” I ask Timothy, beside me up front.

“You’ll see.”

Full Cicada Moon

We’re flying

in Mr. Dell’s plane!

Timothy is sitting behind me.

And I’m sitting beside Mr. Dell—

in the copilot’s seat.

Below us

lies Hillsborough,

the holiday lights,

the drugstore,

Dr. Haseda’s house,

the college and Papa’s office,

and a huge Peace sign shoveled in the quad.

There’s the Trailways bus stop outside the diner,

my school,

Stacey’s house,

and the web of roads

connecting all the places and the people in this town.

Mr. Dell banks right, turning us

away from the sunset

and toward a blueberry sky glittering with stars.

“You fly now,” he says.

“Me?”

“Take the yoke,” he says, and gives me a thumbs-up.

I grip it tight

to steady my shaking hands,

and we fly the plane together.

Then he returns us to the airfield.

Papa and Mama are by the hangar,

jumping and waving.

But I wave harder, my heart fluttering

with joy and peace and love.

I am

a daughter

a neighbor

a friend

a scientist

a poet

a future astronaut.

The stars and the moon,

the sun and all the planets,

every cell, every atom,

every single snowflake

belong in this universe.

And I,

Mimi Yoshiko Oliver,

belong here, too.

This year

I reached for the stars.

One day

I’ll touch the moon.

But tonight

soaring.

am

I

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The story of Full Cicada Moon came to me nearly fully written, told by Mimi Yoshiko Oliver, a sensitive, intelligent, determined, and courageous girl. If you asked Mimi who this story is written for, she’d say it’s for anyone who has big dreams but is short on courage.

I wrote Mimi’s story in wonder and terror and awe, not knowing if I could or should write it. But along the way, the following people gave me the special encouragement and support I needed to turn Mimi’s story into a book:

Josh Adams, my agent, who with one phrase gave me the courage to keep writing this story.

Namrata Tripathi, my editor, whose enormous gift, vision, and love for story sharpened and shaped Mimi’s.

Keiko Higuchi, who generously and enthusiastically read the manuscript, answered my myriad questions, and shared her stories with me. And Caroline Moore for sharing her heart.

Amy Cook, Julie Dillard, Kristen Held, Ellen Jellison, Craig Lew, Sarah McGuire, and Hazel Mitchell—the Turbo Monkeys—and Celeste Putnam and Dene Barnett, for helping set this manuscript in the right direction at a very early stage. And Marcy Weydemuller for the editorial feedback that kept it on track.

Sarah Twiss Howe Clark, my great-grandmother, for faithfully recording the weather and temperature (along with the day’s events) in her diaries for most of her life. When historical weather information wasn’t available, Gramma Clark’s 1969 diary was.

Randi Ring Simons, my heart-sister since our year of tea in Kyoto, for her linguistic advice and her forever friendship.

My children, Julia, Emily, and Andrew, for giving me insight into Mimi’s heart by sharing theirs. And, simply for being.

My husband, Leon, for his steadfast support and his suggestions that added authenticity to Mimi’s story.

And everyone whose courage isn’t quite tall enough for their big dreams. Facing uncertainty and fear, but taking that first small step anyway, isn’t only Mimi’s story—it is everyone’s.

Glossary of Japanese words in

FULL CICADA MOON

Mimi uses many Japanese words in this book, and this glossary explains what they mean. First, here are some tips about how to pronounce them.

• Give each syllable the same emphasis or accent.

• There are five basic vowel sounds in Japanese, and you pronounce them like this:

a sounds like mama

e sounds like red

i sounds like me

o sounds like robe

u sounds like tube (This sound is sometimes almost silent.)

• Some vowels have a line above them (called a macron), and you pronounce them like this:

a means say the a sound a little longer, like “aah!”

o means say the o sound a little longer, like “ohh!”

WORD LIST

“Akemashite omedeto gozaimasu.” – “Happy New Year!” Or, “The new year has opened—congratulations!” You say this the first time you see someone in the new year (and not before January 1). You can also say “Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu,” which means “Please treat me this year as well as you did last year.”

Full Cicada Moon

Full Cicada Moon Found Things

Found Things